I own a range of lenses to do my work and I see each as a painter might see their favorite brushes. Sometimes the strokes need to be wide and sweeping, while at other times, the strokes need to be narrow and precise. To me, each camera lens is like a painter’s brush waiting to be utilized where it’s needed.

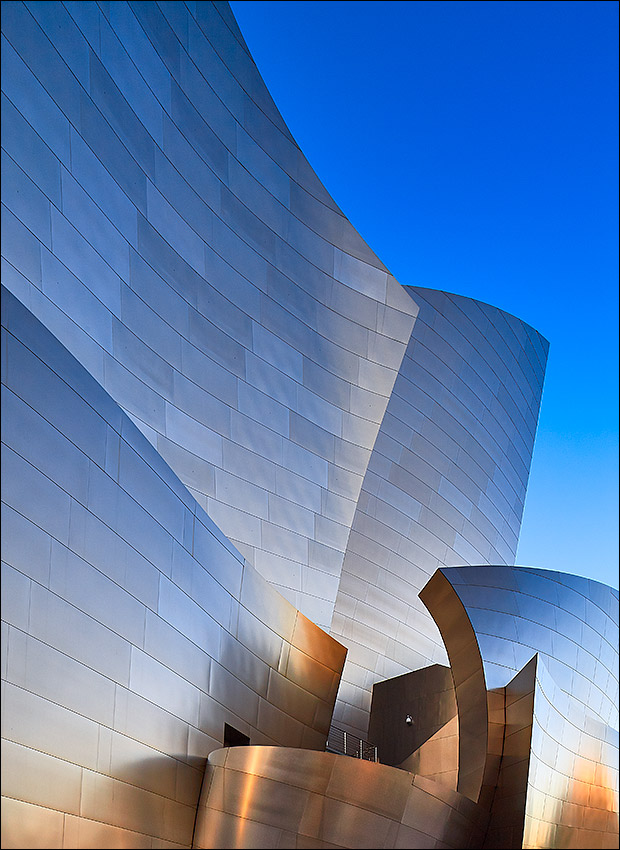

In order to capture the immense scale and curvaceous walls of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, the ideal lens would need to almost wrap around the building’s metal skin to fully show it’s beauty. In addition, the lens would have to be able to properly render the architecture without unwanted distortion or vignetting. And, of course, the lens must be razor sharp.

“I didn’t want the architecture to simply be documented. I wanted it to be felt.”

While considering Frank Gehry’s masterful design, I began thinking about the qualities I wanted to “see” in the final photographs. I wanted the structure to appear immense, precise, shiny, bulbous, and angular. Most importantly, I didn’t want the architecture to simply be documented. I wanted it to be felt.

Thinking this way is called pre-visualization, and it’s one of the best techniques for, “seeing it before you shoot.” Learning to pre-visualize your photographs is how you determine what you’re trying to say to the viewer.

Revealing the brilliance and qualities of the structure was my first objective, but I also wanted the images to flow from one to the next as a series. I decided that by using just a single lens to capture the building from a very intimate perspective, I could achieve both consistency and intimacy.

I had just purchased and tested one of the first available PC Nikkor 19mm f/4E ED lenses from my friend Jody at Robert’s Camera, so I knew it would be a good choice for the project. But, I also believed that this would be the ideal optic for this masterpiece of architecture. Although I could probably also use the PC-E Nikkor 24mm f/3.5D ED or the PC-E Micro Nikkor 45mm f/2.8D ED for certain views, I really wanted to “see” the structure through this one lens.

This building—and Gehry’s equally beautiful Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain—is a significant challenge in photographing shiny metal. Since the building is like a series of immense curved mirrors, it would be illuminated by whatever is reflected in the metal skin. The goal was to use the sky and the sun—very low, or below the horizon—to do the hard work of showing off the detail and shape of the design.

There were two short windows of time where the sky would function as a giant source to illuminate Gehry’s brilliance. Any other time would produce blinding specular highlights on the surfaces of the metal. Not surprisingly, those times were just before sunrise, and just after sunset—which is when all of the photographs were captured.

For projects like this, an absolutely indispensable tool is the Really Right Stuff L-Plates that I keep mated to all of my cameras. The L-Plates are fantastic because they allow me to switch from horizontal to vertical without changing the lens position. The index marks on each plate make it simple to reposition the camera without adjusting the tripod or the head. It may not seem like a big deal, but when the light is changing and speed matters, you’ll be glad you have them.

Joey Terrill is a Los Angeles-based photographer with clients that include American Express, Coca-Cola, Disney, Golf Digest, Major League Baseball, Red Bull, and Sports Illustrated. He teaches workshops and speaks at seminars including the Summit Series Workshops, WPPI, Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar, UPAA Symposium, World in Focus, and Nikon School.